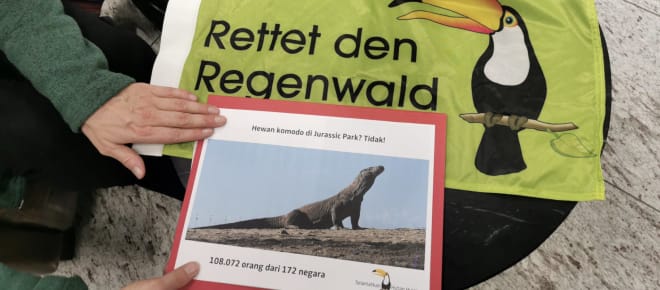

NO to a ‘Jurassic Park’ for Komodo dragons!

Komodo dragons are imposing, timeless creatures that could be straight out of ‘Jurassic Park’ – and that could be their undoing. The Indonesian government wants to lure rich tourists to Komodo National Park with no regard for the Komodo dragons, the stunning underwater world or local communities.

News and updatesTo: President Prabowo Subianto; cc: the governor of NTT province and UNESCO

“Protect the last Komodo dragons – stop the luxury resorts in Komodo National Park!”Will the Komodo dragons end up as an attraction in a ‘Jurassic Park’?

“People here live with the Komodo dragon, which they call ‘ora’ or respectfully ‘sebae’ – twin of the Komodo people. But now Komodo National Park and its inhabitants are in great danger,” warns Umbu Wulang, Director of WALHI NTT, an environmental NGO.

Komodo National Park has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1991. Most of the remaining 3,000 endangered Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) – the largest lizards in the world – live here. Coral reefs, sea turtles, manta rays, whales and dolphins are a testimony to the surrounding sea’s rich biodiversity.

Ideally, Komodo National Park should be closed to the public to permit it to recover from tourism and wildlife trafficking, but now construction projects in the name of ‘ecotourism’ are threatening nature and the local people. Instead of protecting the Komodo dragons, President Joko Widodo wants to drive a new tourism boom.

The developers have named the Geopark project on the island of Rinca ‘Jurassic Park’. The admission fee for the upmarket resort has been set at $1,000. The concessions were awarded to large corporations without prior environmental impact assessments or a focus on science, and without taking existing local concepts for limited tourism into account.

For the local people, a ‘Jurassic Park’ would mean resettlement and the loss of their livelihoods as rangers, souvenir sellers or fishers. For nature, it would entail damage to the ecosystem, a threat to the Komodo dragons and the impact of sewage and sand discharge on the underwater world.

The protests in Indonesia to date have been unsuccessful. “This ‘Jurassic Park’ will destroy nature and the livelihoods of the people who have lived with the Komodo dragons since time immemorial,” says Umbu Wulang, calling on us for international pressure to save the last dragons.

Komodo National Park

Komodo National Park (Taman Nasional Komodo) is located in the Lesser Sunda Islands area east of Bali in NTT province.

In 1977, the islands of Komodo, Rinca and Padar were designated a biosphere reserve by UNESCO. In 1980, the Indonesian government established the Komodo National Park as a protected area for the Komodo dragon. In 1991, it was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The National Park today covers 173,300 hectares, of which about one-third is land and two-thirds is water, distributed among numerous islands of volcanic origin and the sea.

On the three inhabited islands of Komodo, Rinca and Papagarang, a total of about 5,000 people (2017) have lived peacefully with the Komodo dragon for many generations, even before it was scientifically described in 1912 by the head of the Bogor Zoology Museum, Pieter Ouwens.

Komodo National Park is unique in that it is the habitat of the majority of the roughly 3,000 remaining Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis), the largest species of lizard in the world. These giants, which were once common throughout Indonesia and Australia, are the last of their kind. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has therefore listed the Komodo dragon as vulnerable. With its forked tongue, it could pass for a mythical creature.

The Komodo dragon can grow up to three meters long and reach 70 kg. It hunts deer, goats and chickens, as well as eating considerable amounts of carrion. It has a venomous bite that shocks its prey and has an anticoagulant effect. The Javan rusa, a deer native to Indonesia, is its main prey. Komodo dragons are fast and are considered aggressive. Attacks on humans are rare, but do occur occasionally.

Young Komodo dragons are excellent climbers and live almost exclusively in trees. As they grow, they climb less and spend more time on the ground. The people of Komodo therefore build their houses on stilts and keep the outside doors closed.

Komodo dragons can be found throughout the national park on the five islands of Komodo, Rinca, Padar, Nusar Kode (Gili Dasami) and Gili Motang. Keeping track of the population is not easy, as they have been known to swim between the islands. They also live outside of the national park on Flores Island.

In addition to the Komodo dragons, the national park is home to 32 mammal species (including maned deer, wild boar, Javanese monkeys, spotted musang and water buffalo), 37 reptile species and 128 bird species, including the yellow-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea), the orange-footed scrubfowl (Megapodius reinwardt) and the helmeted friarbird (Philemon buceroides).

On land as well as underwater, the region features an unusual landscape. While the islands are characterized by rather barren savannahs, the underwater world is teeming with life and biodiversity, not unlike a rainforest. As part of the so-called Coral Triangle, its marine biodiversity is among the greatest in the world. The waters around the islands are home to 1,000 species of fish, 260 species of reef coral, 70 different sponges, 17 species of whales and dolphins and two species of sea turtles. Since the beginning of the protection measures, blast fishing has been stopped and the area covered with corals has grown by 60 percent.

Although Komodo National Park has the highest protection status, threats from poaching, illegal fishing and wildlife trafficking remain high. The main threats to the Komodo dragon are the fragmentation of its habitat and the decline in its prey due to poaching, despite the efforts of park rangers.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) lists the Komodo dragon in Appendix I, prohibiting any trade in live Komodo dragons or body parts such as skins without special permits.

Despite this, an animal trafficking ring is known to have smuggled 41 Komodo dragons in recent years. The animals were sold online to Indonesian and international buyers at a price of $35,000.

Tourism in Komodo National Park

Tourism began in the 1980s with the establishment of the national park. Since then, the fascinating Komodo dragons have been one of the main attractions. According to official statistics, more than 175,000 people visited the national park in 2018, most of them from abroad. Approximately $1.85 million in revenue was generated by the national park in 2017.

The Indonesian government previously stated that it would close Komodo Island to tourists in 2020 to allow nature to recover. But there is no talk of that now – instead the Indonesian government is pushing to increase the tourism potential of Komodo National Park even further by delegating tourism development to private companies. Since 2012, seven companies have applied for permits to build nature-based tourism facilities. The companies PT Komodo Wildlife Ecotourism (KWE) and PT Segara Komodo Lestari have in some cases already started construction with licenses from the Ministry of Forestry.

These licenses were granted despite massive protests by the local population and environmentalists, without UNESCO’s approval and without an environmental impact assessment of the long-term effects of the construction projects on the unique flora and fauna of the national park.

Luxury tourism is now planned on the islands of Komodo, Rinca and Padar, with an entrance fee of around $1,000 for an annual ticket. Various accommodations, restaurants and an information center are being built.

The local communities that have depended on tourism for decades have been completely excluded in this planning. Until now, they earned their living mainly on the island of Komodo by selling souvenirs and offering guided tours to the Komodo dragons. In future, souvenir stands are to be concentrated only on Rinca Island, two hours away. The previous stalls are no longer compatible with exclusive tourism, it is said.

The tourism boom in Indonesia

Tourism is an important economic factor for Indonesia. This sector is already the third largest foreign exchange earner after coal and palm oil exports - in 2018, tourism generated around $17 billion, according to the BKPM investment authority. In 2018, some 15.8 million tourists visited Indonesia, with six million landing on the island of Bali alone.

With the vision of ‘ten new Balis’ stated by President Joko Widodo in 2016, Indonesia wants to attract even more visitors from all over the world. So far, ten tourism locations have been named. The following four are to be developed as a priority: the world’s largest crater lake Danau Toba on Sumatra, the temple complexes of Borobudur in central Java, Mandalika on the resort island of Lombok, and the port city of Labuan Bajo, which serves as the gateway to Komodo.

Other destinations to be promoted include Belitung on Sumatra, Bromo Volcano in East Java, the Thousand Islands off Jakarta, Wakatobi (Sulawesi), Tanjung Lesung (Banten on Java), and Morotai (North Moluccas).

The Indonesian Ministry of Tourism expects a total of $20 billion to be needed for the planned transport infrastructure such as airports, ports and roads, as well as for hotels, restaurants and leisure facilities. A large part is to come from private investors.

While tourism is slated to play a growing role, more and more air travel, plastic waste, water consumption and inadequate wildlife protection – not to mention the massive expansion of infrastructure – would have catastrophic consequences for the environment and local people. Overtourism has been identified as a growing problem throughout Southeast Asia, including on Indonesia’s own island of Bali.

Regulation No. 14/2016 of the Indonesian tourism ministries states that sustainable tourism must strengthen local communities, preserve culture and protect the environment. Things are very different in actual practice, as the example of tourism development in Komodo National Park shows.

“This tourism policy is a form of ‘green grabbing’ – appropriating the locals’ land under the guise of conservation and environmental protection,” says Eko Cahyono, an Indonesian agricultural researcher.

Threats from construction in Komodo National Park

Construction projects in the guise of ecotourism not only threaten nature, but also the inhabitants of Komodo National Park. The projects envision large-scale infrastructure development that would require a lot of land, water, building materials and energy. Local communities and environmentalists fear that the construction work threatens the endangered Komodo dragons’ way of life and would affect their behavior. It can also impact the dragons’ entire food chain, endanger other endemic species and damage the marine environment through sewage and sand discharge.

The environmental organization WALHI is currently studying the impact on the mangrove ecosystem, a crucial habitat for young Komodo dragons and other animals such as snakes, monkeys and birds.

The best-known construction project is the 1.3-hectare Geopark on Rinca Island, which is expected to cost $6.7 million and has been proudly named ‘Jurassic Park” by its developers. Despite massive protests, construction is in full swing on Rinca Island and scheduled for completion as early as 2021.

According to Indonesian environmental activists, this project violates the National Environmental Protection Act, which prohibits altering the natural landscape in a national park. In addition, well drilling can reduce the availability of water, which is crucial to the survival of animals and plants in this arid region.

The Indonesian government is also planning to convert nature conservation zones for tourism purposes on the island of Padar. In 2012, the Ministry of Forestry opened 303.9 hectares of the island’s nature reserve for tourism. Other islands are also affected by rezoning in the national park in favor of tourism projects.

Private companies have thus been granted permission to manage the habitat of the Komodo dragons and the land of the people living there. The local people, which have so far benefited from tourism, have been completely shut out of the projects.

In 2019, the government was even considering the relocation of entire communities from Komodo Island. The plans to displace more than 1,000 residents were abandoned after fierce protests – but also for cost reasons. Instead, their jobs are simply being eliminated or relocated.

Protest and demands

In 2018, many people in eastern Indonesia (Nusa Tenggara Tengah province, NTT) and environmental groups have joined the #SaveKomodo movement to protest the Indonesian government’s tourism plans and the corporate invasion of Komodo National Park. Due to public pressure, the president had the construction projects of the two licensed companies put on hold. The companies’ licenses remain valid, however.

Local communities and civil society stood up against the plan to relocate around 1,000 people from Komodo Island. Thanks to the massive protests, the resettlement was prevented.

Local communities have called on the government to continue to implement the community-managed conservation plan and limited ecotourism, as the planned luxury construction projects threaten not only the habitat of the Komodo dragons, but also the history, culture, land rights and livelihoods of the local people.

“The local government, together with the national government and tourism companies, must preserve Komodo National Park as a protected area to ensure environmentally friendly tourism that is free from exploitation and commercialization,” said Rafael Todowela, head of the West Manggarai community forum to save tourism (Formapp Mabar), at a protest.

“Conservation must protect the Komodo dragons, not investors,” he added. Instead of focusing on luxury and mass tourism, he called on the government to concentrate more on protecting the Komodo islands, including scientific research on animal welfare and the illegal wildlife trade. The tourism activities of the local people in the peripheral zone of the national park should be strengthened and the inner protected zones should not be converted into further zones of use.

The Indonesian environmental organization WALHI NTT is calling for the revocation of ‘nature tourism use’ licenses to the private sector in Komodo National Park, the formation of fishing groups in the national park, and increased public pressure.

#SaveKomodo demands from President Widodo

- provide environmental impact assessments for the proposed construction projects

- revoke the licenses for ‘nature tourism use’ issued to the private sector

- put the focus on scientific research related to animal welfare

- put an end to the illegal wildlife trade

- do not convert inner protected zones of the national park into use zones

- do not exclude the local population from tourism activities

- continue to implement the concept of community-managed conservation and limited ecotourism

Links

Indonesian Ministry of Investment: All You Need to Know about the 10 New Bali Project in Indonesia

Mongabay: Komodo protesters say no to development in the dragons’ den

Mongabay: Indonesia arrests 7 for allegedly selling Komodo dragons over Facebook

To: President Prabowo Subianto; cc: the governor of NTT province and UNESCO

Dear Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Indonesia has a unique natural heritage with the Komodo National Park. The park is the habitat of the last Komodo dragons, an endangered species. UNESCO declared the area a World Heritage Site in 1991. But now, Komodo National Park and its inhabitants are in danger – construction projects under the guise of ecotourism threaten the protected area.

Instead of promoting upmarket tourism, Indonesia should afford the park better protection.

For the sake of the endangered Komodo dragons, biodiversity and the local people, we support the demands of #SaveKomodo and WALHI NTT and call on you to:

- refrain from construction projects for luxury tourism

- revoke licenses to the involved companies

- promote limited ecotourism hosted by local communities

- take scientific findings into account

- maintain the inner protection zones

- put an end to the illegal wildlife trade

Yours faithfully,

Speaking out on two continents: Environmentalists handed over 108,967 signatures in Jakarta and Berlin calling for protection for Komodo dragons. The petition “NO to a ‘Jurassic Park’ for Komodo dragons” demands that no luxury resorts be built in Komodo National Park.

Work on a “Jurassic Park” tourist attraction is transforming the Komodo Islands in eastern Indonesia and threatening the habitat of the unique Komodo dragons. Excavators have moved in, construction cranes are turning and protests are being brutally suppressed. Our petition to protect the Komodo dragons will be handed over in Jakarta and Berlin on November 10.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is warning of the impending extinction of the Komodo dragons. The organization has classified them as “Endangered” on its new Red List of threatened animal and plant species – a list that is getting longer and longer due to the climate crisis.

Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT) is a province in eastern Indonesia with more than 500 islands, including Flores, Komodo, Sumba and the western part of the island of Timor.

PT Komodo Wildlife Ecotourism and PT Segara Komodo Lestari